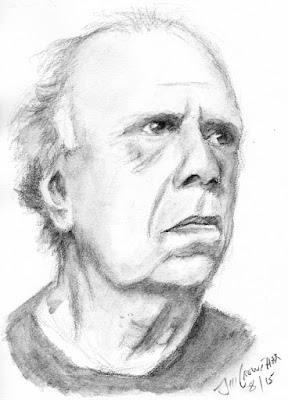

(Self-portrait, 8x6", water-soluble graphite)

As a Princeton senior in the early 60's, I was required to submit a senior thesis in my department, Art and Architecture. Researching and writing the paper took up an entire two semesters, and counted as one course. At the end of my junior year I met with my thesis advisor to discuss my choice of a topic: the noted regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton (one of the triumvirate that included Edward Hopper and Grant Wood). Benton was a longtime neighbor of my family on Martha's Vineyard, and I knew him, his wife Rita, and daughter Jessie well. I had spent a lot of time in his home and studio, and was intimately acquainted with his ideas about art, his work and working process. I had access to sketches, little known paintings of his, and his work in process.

Benton had at one time been one of the most famous and well-paid artists in the country, the first painter to appear on the cover of Time Magazine (Dec, 24, 1934). By the 50's he had gone out of favor with critics, academics, and collectors, as abstract expressionism came to dominate the art scene. That fact alone would have made for any number of possibilities for a thesis, but when I mentioned Benton to my advisor he practically shouted at me, "No! Absolutely not. Thomas Benton is not an artist, he's an illustrator," his tone dripping with contempt.

I folded, and ultimately wrote about 20th century religious art, a subject that had absolutely no attraction for me. It took me years to realize how unfortunate it was I had lacked the courage to defy my professor and write about Benton anyway. In any case I don't think I could have received a lower grade.

I might conceivably have defended Benton against the charge, one that virtually amounted to cultural heresy, but a more interesting approach would have been to use Benton to defend illustration. What were the Old Masters, after all, if not illustrators? Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling is illustration on an epic scale. Raphael was an illustrator. Caravaggio, Velasquez, Rubens, and Rembrandt were illustrators, along with just about every known artist of the time. They didn't merely paint pictures, they told stories: bible stories, myths, historical sagas, contemporary events, inventions.

Illustration and narrative exist as one, and thus, unfairly, narrative got a bad name as well in the late 20th century. The idea that a single image could embody more than an instant, but rather suggest a timeline that in effect had no beginning or end, became anathema to those who considered themselves the snarling watchdogs at the gates of culture. No beginning or end, because who, gazing at any one of a number of iterations of, say, Susanna and the Elders, and without previously knowing this age-old tale of lust, human weakness and hypocrisy, as pertinent now as it was five hundred years ago, can say what exactly set in motion the events playing out before us, or how they will resolve?

(Thomas Hart Benton)

Narrative is such a deeply and intrinsically human impulse that it's almost inconceivable that anyone would declare it off-limits in any particular art form, especially at a time when we are inundated with so many film and television manifestations that rely almost exclusively on cliches, tropes, and shopworn plot gimmicks. The instinct for storytelling goes back hundreds of thousands of years, and it can be reasonably argued that it evolved in us as a survival strategy, enabling early homo sapiens and probably earlier human species as well to contemplate their existence and perpetuate the lives of their ancestors. There is compelling evidence that cave artists found ways to incorporate movement in their work to convey a sense of time passing, much as film animators do today.

No comments:

Post a Comment